Post by Lynn Fuller and originally published by Pacific Birds Habitat Joint Venture

As a Habitat Joint Venture, Pacific Birds promotes habitat conservation and we often report on exciting new acquisitions, easements or restorations undertaken by our land trust partners. Recently we took a look at what is involved after that to ensure that conservation lands are preserved in perpetuity.

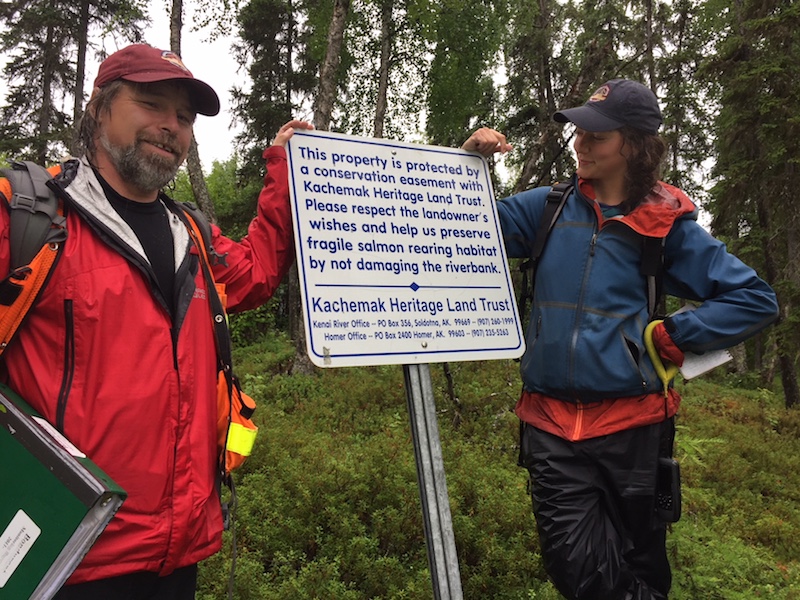

This summer, I joined a monitoring trip on a property on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula to see what Kachemak Heritage Land Trust (KHLT) does on a day in the field. On a rainy afternoon along the Kenai River, Joel Cooper and Courtney Dodge showed me some of the jobs they were doing. They had a large notebook with photos and notes from prior monitoring trips, detailed maps, a chain saw, and clippers. Their commitment to continuing the legacy of the original property owner was immediately apparent.

Dale Bondurant worked with the land trust to put a conservation easement on his property in 1996, in order to conserve the fish and wildlife habitat along the river and the associated wetlands and uplands. Dale has since passed away, but the easement will carry over to the new owner.

The job of ensuring that KHLT’s 41 properties get the attention they need falls upon Joel and Courtney year-round. Twenty-six of the properties are held as conservation easements. Some of those easements allow the landowner to live on or develop the property in a limited way, while maintaining the property’s habitat, cultural or other values. While this is a win-win, it also may mean more time on a property compared to “raw land” monitoring.

I saw this on my visit. Joel and Courtney had 35 photo points to visit that day on the nearly seven-acre property, where they photograph at a known GPS point to monitor change over time. They also had some maintenance work to do on an existing staircase leading to the river. And, they met for some time with a prospective buyer for the property. As Joel explained, it is usually better for the Land Trust to hold an easement rather than owning the property, but new landowners need to understand the “forever” nature of the easement that comes with the property title.

Joel and Courtney maintaining the staircase to the river.

All in all, KHLT holds more than 3,000 conservation acres on the Peninsula. I didn’t ask how many photo points that adds up to, but I am sure it is a lot.

The Habitat Legacy

In Alaska, the Kenai River could be a synonym for salmon. It is a recreational mecca for residents and tourists alike, but the intense summer use has taken its toll on the water quality and the integrity of the river’s shore. River properties like the ones managed by the land trust (as well as many other entities) are helping to ensure that those fish keep returning.

On the banks of the river, Joel and Courtney pointed out a “cable tree”, installed in 2015 with the help of the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Partners Program. The tree helps to stabilize the river bank and provide microhabitats for fish. Joel has already seen young salmon there taking advantage of newly created habitat.

Walking the bluffs along the river, there was a lot of bird activity from fledged songbirds, and gulls overhead in the trees. Dale Bondurant provided a bird list when he donated the easement, but it was a pretty short and non-specific list (such as “Owl”). While the Kenai River salmon runs likely prompted this conservation easement, it is, as usual, really about multiple species.

The Kenai National Wildlife Refuge is close by, and holds and manages substantial acreage on the Peninsula. Their 2018 “Species List” has 2,073 observed native species, 208 of which are vertebrates and many of those are birds. A look at Alaska eBird and area-wide checklists show observations of several species with some level of conservation concern, such as Olive-sided Flycatchers, Lesser Yellowlegs, and Rusty Blackbirds, but a comprehensive bird check list has not been compiled for this property. The habitats are diverse, however, and thanks to the work of the land trust and its many partners, the resident and migratory fish and wildlife will likely be there to count in the future.

The upland forest habitats offer different niches for birds and other wildlife than the river below. Conserving a variety of habitats on properties supports multiple species.