The Rio Grande Joint Venture (RGJV) covers roughly 63 million acres, crisscrossed by seemingly infinite boundaries: natural, cultural, and political. The diverse geography supports about 700 bird species, 75% of which are landbirds. Along with the Sonoran Joint Venture (SJV), the RGJV is the only other Migratory Bird Joint Venture whose geography spans the border between the U.S. and in Mexico. Like the SJV, the RGJV is a binational conservation partnership that supports bird and habitat conservation across borders. The work of our two Joint Ventures intersect in many places, but one of the most pressing issues are birds and grasslands of the Chihuahuan Desert.

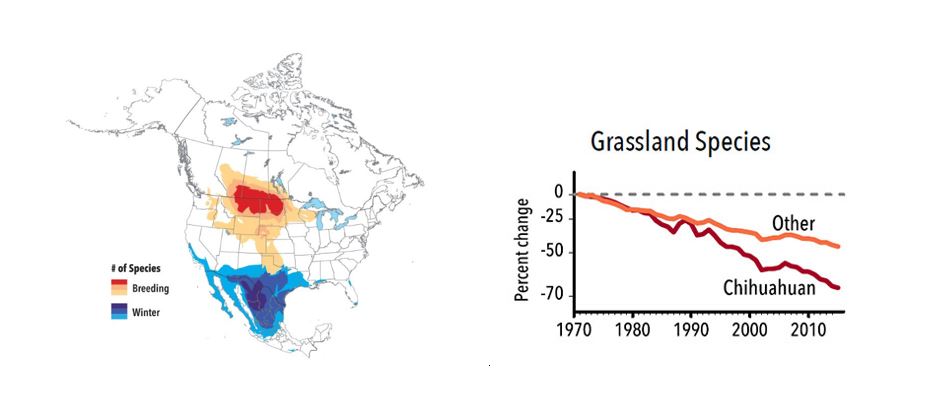

Historically, a vast expanse of native grasslands covered the continent from the prairies of Canada to the high plateau of central Mexico. However, rampant development and land conversion have drastically reduced grassland habitat and threaten the remaining areas. Likewise, grassland bird species have become one of the fastest-declining suites of birds in North America. One-third of all grassland bird species are on the 2016 State of the Birds Report Watch List due to steeply declining populations and threats to habitat. However, the bird populations most at risk are those that breed in the Great Plains of Canada and the U.S., and winter in Mexico’s Chihuahuan Desert grasslands. They are experiencing exceptionally steep declines, a nearly 70% loss since 1970, while other temperate grassland birds have declined by 33% in that time. This is mainly due to habitat conversion to agriculture.

According to RGJV Coordinator Aimee Roberson, “The biggest crises right now within our geography are grasslands and grassland birds. The rate of land conversion of native grasslands to row crop agriculture is happening at an alarming rate.” The 2016 State of the Birds Report estimates that in Mexico, grassland habitat in central Chihuahua will disappear completely by 2025 at the current rate of development and cropland conversion. “That’s only seven years!” Roberson exclaims. “While people are talking about grasslands, I don’t know if they fully understand what we are dealing with here.”

Many grassland species that breed in the Great Plains depend upon the Chihuahuan Desert grasslands during winter. These birds are experiencing populations declines more than double those in temperate areas (left: Map from Partners in Flight, Saving our Shared Birds, 2010; right: Graphic from the 2016 State of the Birds report).

In April 2018, Roberson had the opportunity to speak about grassland conservation to representatives from Canada, the U.S., and Mexico at the Trilateral Committee for Wildlife and Ecosystem Conservation and Management (Trilateral). In the 1980s, the conservation crisis regarding waterfowl population declines and loss of wetland habitat took center stage. Through the Migratory Bird Joint Ventures and international collaboration like the Trilateral, partnerships between government agencies, conservation groups, and private landowners helped halt the declines. Roberson finds many parallels between the waterfowl versus grassland bird crisis. In summing up her plenary talk at the 2018 Trilateral, Roberson says her take home message was, “Grasslands are the new wetlands, and sparrows and pipits are the new ducks. How can we take what we’ve learned in wetland conservation and apply it to the current crisis situation we are seeing in the central grasslands?”

Through ongoing collaboration efforts guided by very active binational board and technical teams, the RGJV and partners are spearheading efforts to bring further awareness to the urgency of this crisis, as well as lead on the ground conservation efforts in both countries. Their focus is not only to protect and preserve the remaining intact grasslands, but also to improve their management. Roberson asks, “What are the strategies we can use for ranchers to stay on their land so that it doesn’t get sold for other uses and converted into something that no longer supports birds or other wildlife? How can we make working grasslands healthier and more productive?”

Restored grasslands on Coyamito Ranch in Chihuahua, Mexico. A different approach to cattle grazing has breathed new life into an area so essential for grassland birds (Photo courtesy of Lilia Vela, Pronatura Noreste and American Bird Conservancy).

Federal, state, and non-profit conservation organizations, as well as university partners, are working to address the different aspects of those questions. Roberson says, “Our partners in Mexico are starting to work with members of ejidos (communal land holdings) and Mennonite communities that farm areas that were previously grassland, and/or adjacent to native grasslands. We are working on finding ways to manage the land to allow for conservation of biodiversity while still meeting people’s needs in terms of working the land for food.” The Joint Venture partnerships use tactics that include both technical and financial incentives for the involved landowners. Earlier this year, the RGJV hosted a binational workshop to visit grassland management sites, discuss strategies, share successes and failures, and create relationships to support future conservation efforts.

The USFWS, Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, Prairie Pothole Joint Venture, RGJV and many other partners recently released A Full Annual-Cycle Conservation Strategy for Sprague’s Pipit, Chestnut-collared and McCown’s Longspurs, and Baird’s Sparrow. These species are a priority for the RGJV and other conservation groups because they are grassland-obligate songbirds whose populations have experienced significant declines and are most at risk. The strategy summarizes current knowledge of the species and identifies priority research, monitoring, and conservation actions to improve population statuses. One important information gap to be addressed is knowledge about use of wintering and migration habitats.

In addition to the species conservation strategy, next steps for the RGJV include developing a “Conservation Investment Strategy” for Chihuahuan Desert grasslands. “With limited resources, we want to be as strategic as possible in where we focus our efforts,” says Roberson. “This plan would help us focus on the most important areas for the suite of grassland birds, but also allow us to think about other wildlife species that are important to our partners.”

To learn more about the work of the Rio Grande Joint Venture, contact Coordinator Aimee Roberson.

This article by Emily Clark, Sonoran Joint Venture, in collaboration with Aimee Roberson, Rio Grande Joint Venture, originally appeared on the Sonoran Joint Venture website.

Top photo: Grassland-shrub Savannah characteristic of the northern Chihuahuan Desert is rapidly disappearing due to encroaching development and conversion to agriculture (Photo by Peggy Greb, U.S. Department of Agriculture, is licensed under CC BY 2.0).